2: Anna is a revelation, bright, loving, polite, dutiful, whimsical, joyful, nearly ecstatic in her religious belief and utterly, it seems, without guile. “I’m going to crack you like a nut, missy,” she thinks. It’s clear to her that her patient is “a little fraud” intent on fooling the world. Most of the residents, and the pilgrims from abroad who are flocking to see the “living marvel,” as one calls her, tend to agree. “It’s a great mystery,” says the family doctor, murmuring some possible theories: that Anna is living on air, or converting sunlight into energy, or receiving sustenance from scent. Everybody seems backward and superstitious the food tastes of peat the nun she meets in the inn creeps her out the “infamous diet of potatoes and little else” has made the inhabitants sickly and pale.Ĭredit. Lib Wright, an English nurse who served in the Crimea under Florence Nightingale, arrives in a tiny village in rural Ireland bringing along an empire’s worth of snootiness and superiority.

Like “ The Turn of the Screw,” the novel opens irresistibly, when a young woman with a troubled past gets an enigmatic posting in a remote place. While the wonder of the title refers to many things, at its core it’s an examination of the mysteries of reason, responsibility and the heart. The book is set in the mid-19th century, but its themes - faith and logic, credulity and understanding, the confused ways people act in the name of duty and belief and love - are modern ones.

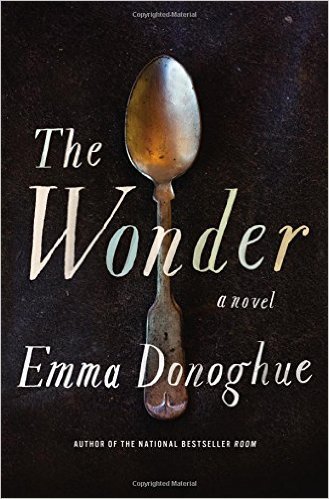

These questions also resonate in the Irish author Emma Donoghue’s fascinating novel “The Wonder,” about a different sort of self-imposed starvation in a different sort of Ireland.

What does it mean to give up the most basic human need in the service of something greater than yourself? Is it an admirable stand, or an abomination? And if you’re an outsider presiding over someone not-eating himself into oblivion, do you have the right, or the obligation, to intervene? That scene - 22½ harrowing minutes, 17½ of them in a single take - appears in “ Hunger,” Steve McQueen’s 2008 movie about how people can turn their bodies into tools of protest and, more profoundly, about the philosophy and morality of fasting. The other is Father Moran, a Catholic priest, who is trying to talk him out of it. One is the Irish Republican Army prisoner Bobby Sands, who is preparing to starve himself to death. Two men sit across from each other in a Northern Ireland prison, locked in an argument so intense it feels like hand-to-hand combat.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)